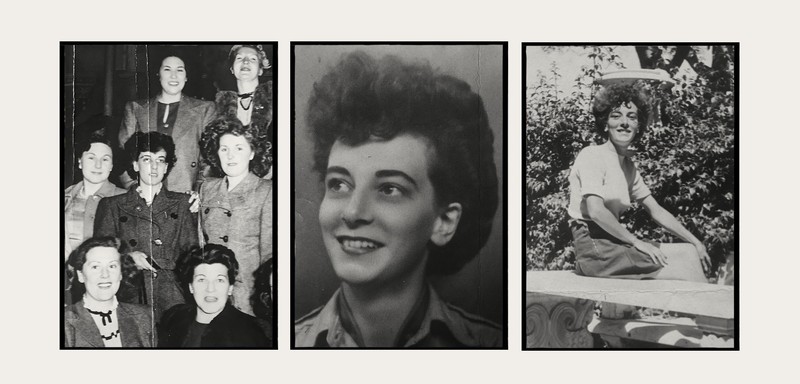

The Gold Edition Meets… Barbara Hurman, WWII Veteran

I grew up in a small village called Seaforth and life was very simple. When the war broke out, I was determined to join up. But I couldn’t until I was 17 ½ so, in the meantime, I was put to work. You couldn’t choose what you did back then – that was down to the Labour Exchange to decide and they sent me to a military factory up the road in Bootle to make bombs. I punched in and punched out, and I hated every minute of it.

My early memories of the war are mostly of the children. By that, I mean the children who were being forced to leave home with their little cardboard box and gas mask, sometimes miles and miles away from everything they knew. Some had happy experiences, some didn’t. Either way, it’s hard to imagine what kind of effect that’s had on them over the years – being forced to leave their mother at such a tender age. As for my generation, war was something we accepted. It wasn’t something we resisted or were shocked by – we just got on with it. Normal life continued for many people.

Finally, with my parents’ permission, I joined the ATS when I was 17 ½ years old. No one was particularly keen on me doing this – my father and a gentleman from the Labour Exchange believed there was no reason for me to join the army and they wanted me to work in the ticketing office for the railway service instead. But I said no, dug my heels in and went to Wrexham.

My time in Wrexham was very different. I can remember one of the first lunches, for instance – I went into the dining hall and there was a big wooden board in the middle of the table piled high with bread. And these girls – who were all around my age – just went wild trying to scramble and get their hands on a bread roll. For a well-brought up village girl, it all came as a bit of a shock! There were only two other girls in my village who had joined up, but they were sent to a hospital in Liverpool, so at times I felt quite far from home and everything I knew.

One of my biggest gripes was that no one taught us to drive in the ATS. It was one of my big hopes when I joined up. After all HM The Queen – or Princess Elizabeth as she was then – ended up joining the ATS in 1945 and lo and behold, she was taught to drive! I met her some years later and when I asked her about it, she just looked a bit blank!

It wasn’t long before people realised I could type and that’s how I ended up in the Royal Signal Corps. We went straight onto the computers – although they weren’t computers like we think of them now – intercepting and trying to translate different messages coming in. While I was in Portsmouth for a while at Fort Southwick, it wasn’t long before I was posted overseas.

I was on night duty before the D-Day landings on 6th June 1944 in Naples. We were waiting to be moved up to Milan. After finishing my duty and going to bed, my friends woke me up early that morning to watch the gliders carrying troops across the channel and the bustling activity in the harbour ahead of Operation Overlord. Little did I know that my future husband, Gordon Hurman, had landed at Sword Beach from a landing craft. We didn’t know each other then – we met after the war ended – but it certainly feels like there was a kind of kismet about it.

/https%3A%2F%2Fsw18.sheerluxe.com%2Fsites%2Fsheerluxe%2Ffiles%2Farticles%2F2022%2F11%2Frememberance-new.png?itok=3PITJ1VR)

Following D-Day, I served in Italy for two more years as part of the Central Mediterranean Forces. I was in Bari, in southern Italy, when news of the end of the war came on VE Day (8th May 1945). I remember it was very strange – they wouldn’t let us off base, and I think it’s because they were worried the young men might go a bit mad – drinking and celebrating, and so on. Oddly, it all felt like a bit deflating; none of us were really sure it was really over.

For the next couple of years, I continued to serve in Italy and was posted to Milan, Caserta, Naples and Padua until 1947 when I came back the UK to be demobbed. I hated coming back to England. All my life I’d wanted to travel, so it felt like the end of a wonderful opportunity. I went and lived with my sister in Barrow-in-Furness for a while and worked at the post office there on the teleprinters. Deep inside, though, I was still determined to go abroad.

People often ask me what I remember most about the war and while there isn’t one particular day or night that stands out in my mind, I tend to say, “I just loved every minute of it.” That might sound odd to some, but it gave me such a lease of life away from the tiny village I’d grown up in. My twin sister, who stayed in the village, said that on VE Day it was completely quiet there – no raucous parties or celebrations. She was the only girl there by that time. Life was so isolated there and I loved that the war gave me the freedom to learn new things and meet new people. I’ll also never forget the time, before being posted to Italy, when about five of us boarded a night train from Paddington station to Scotland – because that was the night I started smoking!

Thanks to the war, I was able to see some of the most beautiful places in the world. Bari was one of my favourites – the buildings were like nothing I’d ever seen before, covered in carvings of cherubs, and I remember this murmur of swallows that lived in the trees outside. That was the thing about war, too – it made you really appreciate things. In Naples, there were these fruit trolleys piled high with huge oranges. It was such a sight – back home, while the war was on, you were lucky if you ever saw a single piece of fruit.

I was able to get a job with NAAFI after the end of the war. About ten years later, I was posted to Egypt and that’s where I met Gordon. He worked in a clerical job for NAAFI too, and when they tried to post him to a different part of the country, they wouldn’t let me go with him unless we were married. So… that’s how that happened. We had our honeymoon in Faiyum – another beautiful place. We eventually came home and lived on the Edgware Road in London.

Together we had three children – two sons, David (a doctor) and Andrew (an artist and curator) and a daughter, who ended up following me into my passion for archaeology. I’d worked at the British Museum in London and worked my way up to being a professional identification expert in the world of ancient pottery – I’ve since had several pieces of my work published.

I admit I’m not really in touch with any of the girls I met during the war. We did try but as the years went by, you realised you didn’t really have that much in common beyond those few years. I imagine it’s a bit like leaving certain jobs nowadays – you think you’ll keep in touch and then, somehow, you drift apart and life goes in different directions. That said, in 2019, I did take part in a British Legion funded theatre project – Recovery Through Arts, where some of us from the Armed Forces Community had the opportunity to tell our stories on stage.

This year's Poppy Appeal runs until Remembrance Sunday on Sunday 13th November. By donating to the Poppy Appeal you’re helping The Royal British Legion provide ongoing vital support to the Armed Forces community, ensuring their unique contribution is never forgotten. Visit RBL.org.uk

DISCLAIMER: We endeavour to always credit the correct original source of every image we use. If you think a credit may be incorrect, please contact us at info@sheerluxe.com.